Constructive Criticism Quiz: What's Your Style Of Delivering Constructive Criticism?

How you deliver constructive criticism will have a huge impact on whether your employees will (or won't) actually make changes and improve their performance. But do you know what kind of feedback you actually deliver? And how that gets received? The way that you deliver your feedback plays a role in whether your people are actually receiving it. Take this constructive criticism assessment to learn more.

Next Steps

It's time to really understand your style of delivering constructive feedback, how well it’s serving you, and how you can provide more effective feedback. We’re going to dig deep into all these topics, but feel free to jump to any section that interests you:

- What is Constructive Criticism?

- Why Constructive Criticism Is Important

- Fewer Than Half Of Employees Know If They’re Doing A Good Job

- Why Leaders Need More Training On How To Deliver Constructive Feedback

- Don't Make Constructive Criticism So Soft That People Miss Your Message

- Stop 'Shirking' When You Give Constructive Criticism

What is Constructive Criticism?

Constructive criticism is interpersonal communication given from one person to an individual or group during a learning or work situation, that’s purpose is to help people to learn from their mistakes in the past, in order to improve in the future.

Why Constructive Criticism Is Important

With fewer than half of employees reporting knowing if they’re doing a good job or not, it highlights that they are receiving little feedback from their managers or employers about their progress. One key to fixing this problem is by providing feedback much more frequently. When managers withhold feedback, it allows small issues to build into bigger issues, and it deprives employees of the chance to make corrections. Leaders who let issues pile up, experience increased anger and that translates into bigger and more destructive employee conversations.

Fewer Than Half Of Employees Know If They're Doing A Good Job

A Leadership IQ study called “Fewer Than Half of Employees Know If They're Doing A Good Job” found that only 29% of employees say they "Always" know whether their performance is where it should be and that well over half of employees “Never,” “Rarely” or “Occasionally” know.

One of the core functions of a leader is to provide on-time constructive feedback about employees’ performance. If that were happening, we’d see close to 100% of employees that know whether they’re doing a good job, but the data shows clearly that this isn’t the case.

The fact is, around nine out of ten managers have avoided giving constructive feedback to their employees for fear of the employees reacting poorly.

And is it any wonder that an employee would react badly to getting constructive feedback when less than half of them know if they’re doing a good job?

If you don’t know whether your performance is where it should be, there’s a good chance that you’re not going to be happy when your boss comes up to you and bashes you with some very tough feedback. Especially, if managers only share feedback once a year.

One of the ironies is that if leaders were giving more regular feedback about employees’ performance, they could do it in small, bite-sized chunks and avoid may of the big tough conversations that cause so much stress. And most employees would really like receiving feedback, in order to know that they’re doing a good job.

People know that it’s tough to improve and be successful in their careers if they’re not receiving sufficient constructive feedback. Another irony here is that when constructive feedback is given regularly, and not left to build up for a year or more, employees actually handle it pretty well.

For example, we know from the quiz “How Do You React To Constructive Criticism?” that around 39% of employees react to constructive criticism by systematically dissecting every step leading up to the thing they just got criticized for. They don’t freak out, instead, like a process engineer looking to root-cause a product defect, they just want to understand and correct the underlying issues in order to improve their performance.

The first piece of advice for fixing this problem is to give feedback much more frequently. One of the worst ways a leader can falter is through withholding feedback.

First, it means that small issues build and build into bigger issues. If every leader gave constructive feedback within hours of a problem, each conversation would be pretty small and easy.

But, when we let issues pile up, leaders get angrier and that translates into a bigger, and more uncomfortable, conversation with the employee because the feedback can feel more like negative feedback or even a personal attack. That would translate into destructive criticism rather than constructive criticism.

Second, when we withhold feedback, we’re depriving the person of ways to jump in and improve things. As I just mentioned, 39% of employees respond to constructive criticism by jumping in and correcting underlying problems. But how can they do that when they don’t even know that there is, in fact, a problem?

Here’s an interesting exercise; ask your employees how often they would like to receive feedback from you about their performance. Ask them if they’d like to get feedback yearly, quarterly, monthly, weekly or even daily. I can virtually guarantee that no good employees will say they want feedback yearly; that’s way too infrequent. Hardly anyone will say quarterly, for the same reason.

Most good employees will choose monthly or weekly, with some high-achiever types opting for daily. Now, I did say that no ‘good’ employees will choose yearly feedback. The reality is that you might get one or two people who say ‘yearly’ just as you might get one or two employees who say they ‘never’ want feedback.

Inevitably, those folks are not going to be your best people. In fact, the employees who give those kind of wiseacre responses are typically what I call Talented Terrors; they have great skills but lousy attitudes. They’re “emotional vampires”; they won’t actually suck your blood, but the frustration of dealing with them will suck the life out of you.

Once you discover how frequently the majority of your good employees want feedback, provide it that frequently, and make sure that it is constructive feedback. One of the better practices that high performing leaders often adopt is monthly coaching sessions with their people.

Each month, have a communication session where you discuss the employee’s high and low points, learning opportunities, and areas where they could improve their performance.

This conversation doesn’t obviate the need to still provide real-time performance feedback, but it does offer a guarantee that your people won’t have to wait all year to learn whether their performance is where it should be.

One final note; high performers generally love these conversations, but your low performers may not. If you’ve got employees who know that their performance is subpar, and they’re skating by hoping that no one else notices, receiving feedback, particularly, criticism, probably won’t make them happy.

But that’s all the more reason to let them know that you are aware of their performance and that you’re going to be paying much closer attention and addressing this issue much more frequently.

Why Leaders Need More Training On How To Deliver Constructive Feedback

While giving constructive feedback is not the favorite part of any leader’s job, it is an absolutely necessary function. But new data show that too few leaders are effectively fulfilling that function.

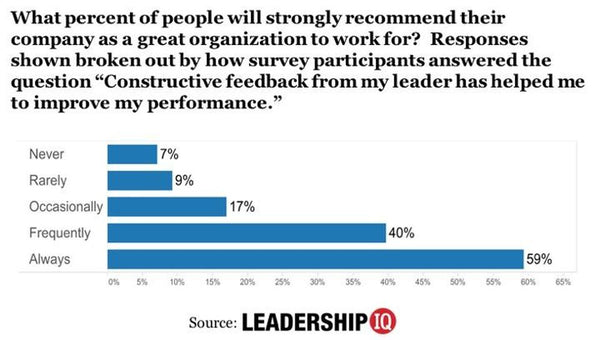

Leadership IQ recently surveyed more than 27,000 people, and among the dozens of questions, we asked people to rate the statement “Constructive feedback from my leader has helped me to improve my performance.”

Only 20% of people say that their leader will “Always” share constructive feedback that has helped to improve their performance. Meanwhile, 20% of people say that their will leader “Never” share constructive feedback that has helped to improve their performance.

Even if we combine those who say that their will leader “Always” (20%) or “Frequently” (23%) share constructive feedback that has improved their performance, that still leaves 57% who feel that their leader has not performed well on this issue!

Let this data sink in for a moment; 57% of people are essentially saying that their leader is not doing a good job delivering constructive feedback that will improve their performance.

How much improvement would we see from employees if they received more or better feedback from their leader? How many good people have quit because they didn’t feel like they were showing improvement at their job (because they weren’t getting enough feedback)?

Surprisingly, Employees Want More Feedback.

Even though it might seem like employees wouldn’t want their leader giving them lots of constructive feedback, that’s just not true. In this same study, we also asked people whether they would recommend their company as a great organization to work for.

And here’s the shocking finding:

- 59% of employees who say that their leader will “Always” share constructive feedback that has improved their performance will strongly recommend their company as a great organization to work for.

- By contrast, only 7% of employees who say that their leader will “Never” share constructive feedback that has improved their performance will strongly recommend their company as a great organization to work for.

Essentially, if someone says their leader will “Always” share constructive feedback that has improved their performance, they’re nearly 8 times more likely to recommend the company as a great employer. It’s hard to think of better business advice for training leaders than this!

At most companies, leaders do receive training. But for all the courses they attend, most leaders are not mastering the people skills, like delivering constructive feedback, that are required to successfully manage a team.

For example, even at the most advanced companies, I still hear HR and OD people complain that they regularly get calls from managers about poor performing employees. And when the HR/OD executives ask, “what kind of constructive feedback have you given the employee?” the answer they share is either “I haven’t” or “well, the employee just won’t listen.” And those are pretty basic issues.

Most managers have never heard of concepts like cognitive dissonance or the Dunning-Kruger effect, which explains why some people think they’re great even when their work is terrible. Yet these are psychological and cognitive blockages that prevent employees from hearing and providing constructive feedback. And if a leader wants to be an advanced practitioner of providing feedback, they need to understand concepts like these.

Even the most senior leaders can use help on these issues. For example, one of my studies called “Why CEO’s Get Fired,” found that the top executive often gets fired for issues unrelated to financial performance.

In fact, we found that reasons for CEO firings included ‘poor change management’ and ‘tolerating low performers.’ Those are very soft skills and even CEOs are typically undertrained to perform them well.

It’s pretty common for a top-performing individual contributor to get promoted into a management role on the basis of their past exemplary performance. And while that’s probably not going to change anytime soon, there are two problems with that model.

First, the skills necessary to be a great software engineer, salesperson, financial analyst, or whatever, are very different than the skills required to be a great leader. They’re not necessarily mutually exclusive, but they are radically different.

Second, it takes years of formal and on-the-job training to be a great software engineer, salesperson, financial analyst, or whatever. But when we promote these high performers into management work, they often receive little more than a budget binder and a course on how not to get the company sued. And even when they do receive some putative management training, it’s often not advanced enough to prepare them for the subtle and difficult situations they’re likely to face in the real world.

So remember, fewer than half of people think their leader is doing a great job of sharing constructive feedback that will improve their performance. And for the minority who are receiving feedback that’s constructive, they’re 8 times more likely to recommend the company as a great employer.

If you think the leaders at your company could use more skills development, giving constructive feedback would be a great place to start. Your employees’ success and well-being depend upon it.

Don't Make Constructive Criticism So Soft That People Miss Your Message

Effective constructive criticism requires a delicate balance. When criticism is too harsh, recipients shut down emotionally, get defensive, and fail to find positive motivation in the words being said. And when criticism is too soft, recipients fail to hear the message that they really do need to change and improve.

It’s a difficult balance to maintain, and only a minority of leaders strike it effectively. Oftentimes it’s leaders who use a Complimenting style of delivering constructive criticism that can benefit from toughening up their feedback. Differently, leaders who have a Stern style of delivering constructive criticism (if people become defensive when you give feedback this may be you) may need to dial it back.

Historically, I’ve found more incidences of managers delivering criticism that’s too harsh, and might be called destructive criticism, but lately I’m seeing a bigger problem with criticism that’s too soft. I recently conducted a 3-question quiz that assessed how over 1,800 leaders share constructive criticism.

One of the questions asked respondents to indicate which statement best represented them, and here are the 4 possible choices:

- Employees need to know the cut-and-dried facts about whether their performance was bad, good or great. But I don’t get into emotional discussions of my feelings about their performance.

- I don’t have time to give constant feedback. If my employees want to know about the quality of their performance, they can schedule time to talk to me.

- Of course some employees feel criticized or offended by my words. Constructive criticism is supposed to be tough. It’s constructive, but it’s still criticism.

- I make constructive criticism easier to hear. I often use a compliment sandwich or Feedback Sandwich (a nice compliment, followed by a bit of criticism, followed by another nice compliment). If the employee shuts me out, they won’t improve.

About 31% of respondents chose Answer #1, which is good because that’s the answer associated with the most effective constructive criticism. Only 3% chose #2 (a laissez faire approach) and 14% chose #3 (a harsh approach). What concerns me is that 51% of respondents chose #4. Now, some of the sentiment in that answer is fine; you don’t want employees to shut you out.

But the compliment sandwich, sometimes called a feedback sandwich, while it typically comes from good intentions, is rarely, if ever, a good approach to delivering constructive criticism.

Imagine your boss calls you in to deliver some constructive criticism in the form of a feedback sandwich. They might say:

“You're a world-class talent, the absolute best. You're probably the smartest person in the department. Now, you've been pretty nasty during our weekly meetings, and it's causing some hurt feelings. But I'm saying all this because you’re just such a talented person and I want to see you shine.”

All I hear in that message are the positive comments and suggestions that I’m really smart and talented. (I wrote that sentence and it’s honestly hard for me to remember the criticism in the middle without rereading it).

The constructive criticism is incongruous with all the compliments, and as a practical matter, people don’t usually remember the stuff that comes in the middle. This is what psychology calls the serial position effect.

If, for example, you were asked to remember a list of words, you’d likely remember the words at the beginning of the list and the words at the end of the list. And you’d probably forget the ones in the middle. It’s worth noting that, depending on the study, the recall for the words at the end can be 3-5 times higher than for the words in the middle! (If that doesn’t make the case for not sandwiching your constructive criticism, I’m not sure what will).

I’m not suggesting that you should call employees into your office and verbally bludgeon them. Bullying, with its destructive criticism and comments, is equally ineffective.

Far more helpful is taking the opportunity to adopt a more Factual style of delivering constructive criticism. Our research shows this is the most effective feedback as it helps people in accepting constructive criticism and influences a positive growth mindset that gets results.

When given a choice of receiving feedback delivered with some positive feedback or compliments OR delivered as just the candid unvarnished facts about what was wrong, a whopping 63% of people say they want their negative feedback to be just candid unvarnished facts!

One of the reasons why people would prefer the candid unvarnished facts is that they’re tired of people giving them a compliment to soften them up and then nailing them with the criticism.

The negative Pavlovian response, coupled with the seeming disingenuousness ways of mixing compliments and criticism, is awfully frustrating. Additionally, when we get just the facts about our performance, without any emotions or interpretations, the words carry more weight and importance.

For example, telling an employee “you know I love your work, just one thing I need more of is for you to pay attention to the details so your reports don’t have typos” is an interpretation, not a fact. A fact would be “your report has 3 typos.”

The only way to help this employee to focus and to be super successful is to get them to understand the importance of the typos. But softening the message about the typos with a compliment dilutes the core message. When we strip away the interpretations and emotions, and just deliver facts, the recipient doesn’t get confused or get wrong ideas; they simply go fix the typos (and hopefully don’t repeat the same error) and ultimately improve and become much more successful.

As leaders, we have an obligation to help our employees improve. And it’s abdicating our responsibilities to sugarcoat and water-down our messages to the point where employees don’t understand the behavior or performance element that they need to improve.

Stop 'Shirking' When You Give Constructive Criticism

To be a great leader, you can’t fear being seen as the bad guy/gal. And I’m not just talking about an obvious ‘bad guy/gal’ situation like telling someone “you’re fired” or “you’re not getting a raise this year and here’s why...” I’m also talking about simple situations like telling someone “I need you to change the way you submit that form.”

To be a great leader, you’ve got to occasionally give constructive criticism, or other tough feedback. And when you do, you’ve got to own it, even if that means being seen as the bad guy/gal.

Shirking is the opposite of owning your feedback. It’s basically saying to an employee “Listen, I think you’re doing a great job. But Bob, the new VP, he’s not so happy with some of your work and we’re going to have to talk about that.”

Shirking is giving tough feedback but ascribing it to someone else, so you don’t have to feel like the bad guy. And, not surprisingly, shirking usually backfires.

Shirking shows up all over the place. For example, you hear it in situations like these:

- “You know I’d give you an 8% raise if I could, but the new VP is staying firm on 2%.”

- “You know I don’t have a problem keeping you on the account, but the CEO must have overheard something you said to the client. The CEO made the call on this one. I don’t really have any control.”

- “We’re pulling back on remote work hours. I think it’s been working out fine, but the HR team wants folks back in the office.”

Ascribing our feedback to someone else is an abdication of our responsibility as leaders. And shirking a) ruins employee relationship building, b) destroys leadership camaraderie and c) encourages a culture of blame in the organization.

Having the guts to give your people tough news doesn’t make you the enemy. Rather, it makes you a leader who helps your people to grow and to develop and to achieve great things.

When you toss responsibility for that news to someone else, the lesson gets lost. The only thing the employee learns is, “Wow, that new VP (or whoever) is a real jerk.” And that can unleash a whole new set of behavioral problems as the employee now sees that new VP as the enemy instead of the exciting new leader who is going to turn the company around.

Leave the new VP (or CEO or HR team) out of it and approach the feedback with fact-based communication that tells your people “awesome performance looks like X,Y and Z, and your performance doesn’t look like X, Y and Z, so let’s talk about how to get you to awesome.”

Owning feedback in this way, instead of blaming someone else, carries weight. It lets your people know you’re serious, it engenders respect, and it makes people accountable to making the desired behavioral changes. It’s the foundation on which employee/leader relationships are built.

Shirking just makes employees feel defensive and mad at someone else. Shirking can also make your fellow leaders mad at you. The peers and bosses you throw under the bus might not enjoy playing your scapegoat, even if the tough feedback did originate with them.

Let’s say Pat, the new VP, really did walk into your office. And Pat really did say “Your guy is screwing up communication with the client and I want him off the project.” Throwing Pat under the bus isn’t going to win any points with Pat. The odds are pretty good that Pat went to you instead of directly to the employee for a reason: an invitation to do your job.

Shirking positions you as someone who can’t do the job, who blames, or even worse, who stirs up organizational drama. Your peers and bosses will lose trust in you and will no longer share the valuable constructive feedback that you need to do your job well. Shirking destroys leadership camaraderie.

Finally, if we throw Pat under the bus, or the new CEO, or whomever, we have basically said to our employees “It’s OK in this organization to throw people under the bus. Look at how I just did it! So go ahead and blame. Forget all that stuff we’ve been spoon-feeding you about being accountable. In this workplace, blame is the game!”

The research on this is clear: blame is contagious. The more we blame others the more the people around us are going to feel that it’s OK for them to blame others as well.

A final piece of advice: if you have critical feedback to give, you’ve got to own that feedback. Don’t throw your colleagues or bosses under the bus by shirking.

Stick to fact-based communication. It will bolster your bravery by allowing you to speak candidly without making people angry so you can turn tough conversations into coaching conversations that result in positive behavioral change.